In this biweekly series, we’re exploring the evolution of both major and minor figures in Tolkien’s legendarium, tracing the transformations of these characters through drafts and early manuscripts through to the finished work. This week, by special request, we’re looking at Haleth, one of the great heroes of Middle-earth’s early days. She rallied her father’s people on the brink of destruction and later became one of the only recorded chieftainesses of the Edain, and a powerful advocate for the women of her people.

In the beginning, Haleth was a male character, one of the three Fathers of Men who came into Beleriand after Bëor (The Shaping of Middle-earth, hereafter SM, 211). His people were the last of the Elf-friends to remain in that area, and perhaps, Tolkien at one time suggested, were protected by the magic of Melian (SM 152). The People of Haleth were broad-shouldered and short, with light hair and eyes. They tended to be “slower but more deep [in] the movement of their thoughts” than the other of the two great Houses. Their “words were fewer, for they had joy in silence, wandering free in the greenwood, while the wonder of the world was new upon them” (The Lost Road, hereafter LR, 303). They spoke a language called Taliska, which was influenced by the speech of the Green Elves (LR 195)—and apparently, Tolkien (characteristically) went so far as to devise a grammar of this obscure tongue (LR 210), though to my knowledge it has never been published.

In these early tales, the People of Haleth fostered Húrin. Here the first inklings of the visit of Huor and Húrin to Gondolin emerge, only in the earliest stages it’s Haleth and Húrin (at this time only a boy) who stumble into some of Turgon’s guards, who then bring them to the hidden city. Later, they beg leave to depart when they hear of the coming storm of Morgoth (SM 357, 383).

But all this changes somewhat abruptly. Tolkien begins striking through references to Haleth as one of the three Fathers of Men: enter Haleth, reborn as the formidable chieftainess of the Haladin.1

Descriptions of the People of Haleth primarily remain the same. They’re still physically broader and shorter than their kin, still introspective and detached, still proudly committed to their own personal freedoms and their clannish lifestyle. But they are no longer recognizable as one of the three great houses of Men, but rather an offshoot of a larger population. They “did not live under the rule of lords or many people together, but each homestead was set apart and governed its own affairs, and they were slow to unite” (The War of the Jewels, hereafter WJ, 221). When the assaults of Morgoth become too great to weather alone, Haldad, a man “masterful and fearless,” attempts to unite the Haladin (WJ 221). They fall back to a defensible angle of land between the rivers Ascar and Gelion and barricade themselves there, using the bodies of water as natural borders and building a stockade on the third, open side in order to fence themselves against the outside world.

Orc raiders appear, however, and the Haladin are sorely besieged until a food shortage drives Haldad to lead a sortie against the Orcs. The sortie is unsuccessful, and Haldad is killed. When his son Haldar sallies out “to save his father’s body from their butchery,” he is slaughtered as well (WJ 222). And finally, we’re reintroduced to Haleth.

“Haldad had twin children,” we’re told: “Haleth his daughter and Haldar his son; and both were valiant in the defence [sic], for Haleth was a woman of great heart and strength” (WJ 221-2). Upon the death of her father and brother, Haleth rallies. With nothing more than the iron strength of her will, she holds the people together and withstands the Orcs’ assault for another seven days. During this time the Haladin are stretched to the breaking point of despair. Seeing no hope, “some cast themselves in the rivers and were drowned” (WJ 222). Still Haleth maintains the stockade, despite the dwindling forces and supplies. Then comes the last gasp: The Orcs break through the crumbling stockade and finally enter the protected angle of land between the rivers. All hope is lost.

Suddenly, unexpectedly, we’re given a small eucatastrophe. The Haladin hear “a music of trumpets, and Caranthir with his host came down from the north and drove the Orcs into the rivers” (WJ 222). Caranthir, the fourth son of Fëanor, was known for his harsh temper and his anger like quicksilver, so it’s no surprise that he had ignored the Haladin until now. It’s implied that he thought little of the Edain, underestimating their strength and prowess. In fact, though he’s living nearby, just to the north, this is the first interaction between his people and those of Haldad. He sweeps in at the last moment, claims the victory, and in the process is impressed by the strength of this ragged band of Edain. He extends welcome to Haleth and offers her weregild for the deaths of her father and brother—a strange move which perhaps suggests that he realized an earlier arrival on his part would have saved many lives. Then, “seeing, over late, the valour there was in the Edain, he said to [Haleth]: ‘If you will remove and dwell further north, there you shall have the friendship and protection of the Eldar and free lands of your own'” (WJ 222). His offer is a generous one as far as it goes, but the narrator’s preceding comment—that he made the offer because he saw at last how valiant were the sons of Men—suggests Caranthir was expecting them to offer as much protection as he was claiming to give.

Haleth is unmoved. She presumably refuses the weregild (the text doesn’t explicitly say, though it’s implied), and coldly thanks Caranthir. In this moment she is “proud, and unwilling to be guided or ruled, and most of the Haladin [are] of like mood” (WJ 222). I imagine her standing before the tall, harsh Elf-lord: around her is the wreck of the stockade; her people preparing the dead for their final rest; the fires that devour the last of the homesteads casting shifting shadows across her battle-worn, exhausted face. But she stands straight and proud, young and dwarfed by the tall Noldor, and refuses his overtures: “‘My mind is now set, lord, to leave the shadow of the Mountains and go west wither others of our kin have gone'” (WJ 222).

So the Haladin gather their scattered and shattered people and prepare to depart the angle of Ascar and Gelion. They choose Haleth as their chief, and she leads them out of the destruction into Estolad. Here they become even more removed from those of their kin, and in recognition of Haleth’s leadership they are “ever after known to Elves and Men as the People of Haleth” (WJ 222). Eventually, though, Haleth desires to continue her westward way; and “though most of her people were against this counsel, she led them forth once more; and they went without help or guidance of the Eldar, and passing over Celon and Aros they journeyed in the perilous land between the Mountains of Terror and the Girdle of Melian” (WJ 222). But it was a dangerous path to take without elvish aid, according to the narrator, and “Haleth only brought her folk through it with hardship and loss, constraining them to go forward by the strength of her will” (WJ 222). But even here her people continue to dwindle. They attempt to pick up the threads of their old life in a new land, but many regard with bitterness their past journey, and some break away and dwell deep in Nargothrond, the kingdom of Finrod Felagund. Haleth takes her remaining band and settles in the Forest of Brethil. Later some of her scattered folk return here, but for the most part the People of Haleth never recover from that first assault from which Caranthir saves them.

As might be expected, though, Thingol isn’t happy that mortals have settled in his lands; Brethil, though outside of the Girdle of Melian, is still claimed as part of his realm. He attempts to force them out, but Finrod Felagund (presumably through the refugees wandering in his own lands) hears the tragedy of Haleth and her people. Finrod, as a friend of Thingol, is able to influence the stern king of Doriath, who agrees that Haleth is allowed to “dwell free in Brethil upon condition only that her folk should guard the Crossings of Teiglin against all enemies of the Eldar and allow no Orcs to enter their woods” (WJ 223). Haleth is offended by Thingol’s offer, and she sends back a cutting reply: “‘Where are Haldad my father, and Haldar my brother? If the king fears a friendship between Haleth and those that devoured her kin, then the thoughts of the Eldar are strange to Men'” (WJ 223). In this passage we see simultaneously Haleth’s pride and her sorrow. She has the love and devotion of her people; many specifically wish to live only under her rule, but she seems painfully aware of the fact that her people are living as refugees in a strange land. They’ve fallen from past greatness; her invocation of the deaths of her father and brother represents the enduring wounds of a great loss, but it also subtly rebukes the Eldar for expecting protection from a people that was nearly annihilated on the outskirts of an Elf-lord’s lands. Despite Haleth’s haughty reply, though, she maintains at least a semblence of an alliance with the folk of Doriath (The Peoples of Middle-earth, hereafter PM, 308).

Here they become a people apart. Many adopt Sindarin for trade with the Eldar, but not willingly, and those who had no occasion to travel abroad retain their own language (presumably still Taliska). They “did not willingly adopt new things or customs, and retained many practices that seemed strange to the Eldar and the other Atani, with whom they had few dealings except in war” (PM 308). Nevertheless they’re regarded as important allies, though they are only able to send out small bands, and are “chiefly concerned to protect their own woodlands” (PM 309). In complete disregard for their small numbers, they defend their corner of the world so fiercely that “even those Orks [sic] specially trained for [forest warfare] dared not set foot near their borders” (PM 309).

Haleth lives in Brethil until her death. Her people bury her with reverence in a “green mound […] in the heights of the Forest: Tûr Daretha, the Ladybarrow, Haudh-en-Arwen in the Sindarin tongue” (WJ 223). But she left her enduring mark on her people: one of the strange customs, misunderstood by both the Eldar and other Men, “was that many of their warriors were women.” In fact, Haleth herself, “a renowned amazon,” maintains “a picked bodyguard of women” (PM 309).2 In another unusual move, Haleth never marries, but rather remains the chieftainess of her people until the end of her life: and her position opens possibilities for other women. Tolkien wrote that though most of the eldest line of the house were men, Haleth made it clear that “daughters and their descendants were to be eligible for election” when the time came to choose a new leader (WJ 308).

Haleth’s choices, especially her advocacy for her fellow women, are inspiring, but her story is also pervaded by a lingering sense of sadness and denial. She sees her father and brother slaughtered, but instead of collapsing under grief and despair she allows the weight of leadership to fall on her shoulders. She resists the attempts (unconscious or otherwise) of great leaders like Caranthir and Thingol to belittle either her or the sacrifices of her people, and instead devotes herself to protecting and leading a people that struggles to regain its footing after near-destruction. Her will never wavers and she never divides her attention. It’s also likely, since she never had children of her own, that she took in her brother’s son and taught him to be a good chieftain.

In some ways, Haleth had charge of a doomed people, and that in itself is tragic. She holds them together for a time, but after her death they slowly scatter and become a lesser people. Kind-hearted Branthir, who takes in Níniel and attempts to protect her from Túrin’s destructive influence, seems to be the last named chieftain of the People of Haleth; ultimately, he is cast out and denounces the people that rejected and shamed him (Silmarillion 227), and is slain in anger by Túrin.

It’s a poor legacy for a great woman. Haleth, I believe, epitomizes the kind of spirit Tolkien so admired: stern resistance in the face of despair, and a commitment to honor and strength even when all hope is lost. Haleth had to know her people would never recover from the slaughter between the rivers; and yet, she continues to respect their sacrifices by defending them and their honor whenever necessary. Not only that—because of her example, her people clung to the “strange” practice of allowing women to hold positions of authority and maintain influence in both martial and political matters.

We need stories of women like Haleth, now more than ever. In fact, I’d love to see a film made of her life. Can you imagine it? A young but powerful woman takes charge of her people in the most dire of circumstances, refusing to simply become a vassal of some great lord, and eventually, despite the fact that her folk are fast-failing, leads them through tragedy to become a people that even specially-trained units of Orcs won’t dare to approach. Haleth makes mistakes, yes, but she’s a powerful and inspirational figure whose story—even, and perhaps especially, its tragic ending—deserves attention and respect.

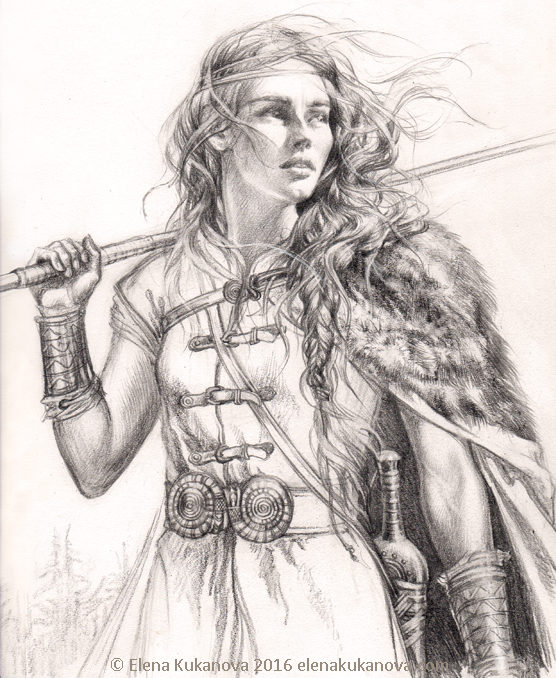

Top image: Haleth by EKukanova

Megan N. Fontenot is a dedicated Tolkien scholar and fan who is currently living a somewhat nomadic life, not unlike Haleth herself, while between graduate programs. Feel free to request a favorite character in the comments!

[1]I discuss the original Haleth because Christopher Tolkien specifically writes that “Haleth ultimately became the Lady Haleth,” implying to me that we ought to read them in conjunction.

[2]Though there is nothing in the text to suggest it, I can’t help but hope stories of Haleth were told in years to come, and were heard by someone like Éowyn. (There are some interesting similarities between Haleth and Éowyn, including the fact that Tolkien identifies both as “amazons.”)

My favorite under represented Tolkien character. Thank you!

A precious post really appreciated by an old fan of Tolkien’s masterwork like me

Yay, a Haleth article!

Thanks for this :)

It seems to be a feature of Tolkien’s background in old Germanic literatures – Bergthora, Njal’s wife in the Story of Burnt Njal (Brennunjalsaga) is not a shrinking violet; Fastrada, Charlemagne’s third?/fourth? wife, took an active part in managing the Holy Roman Empire; Gudrun aka Kriemhild, who brings Atli down for his crimes against her brothers … and so on and so forth … I guess he suddenly realized that he was missing out on part of the specific “tang” of heroism in his favourite literature by ignoring women and their heroism.

I don’t think Tolkien ever ignored female heroism, I mean Luthien alone disproves that. But there are other Elven ladies, Galadriel who is a bit of an Amazon herself, Aredhel who fights her was out of the mountains of terror, Idril Celebrindal rounding up refugees and sending them through her escape tunnel as Gondolin burns, even Finduilas has the guts to stay in Nargothrond rather than flee.

Among mortal Women we have Emeldir Man-Heart who leads the people of Barahir to refuge while her husband and son stay to fight. Poor Doomed Morwen and her gutsy daughter Nienor. And of course Haleth.